Monkeyphoto 9

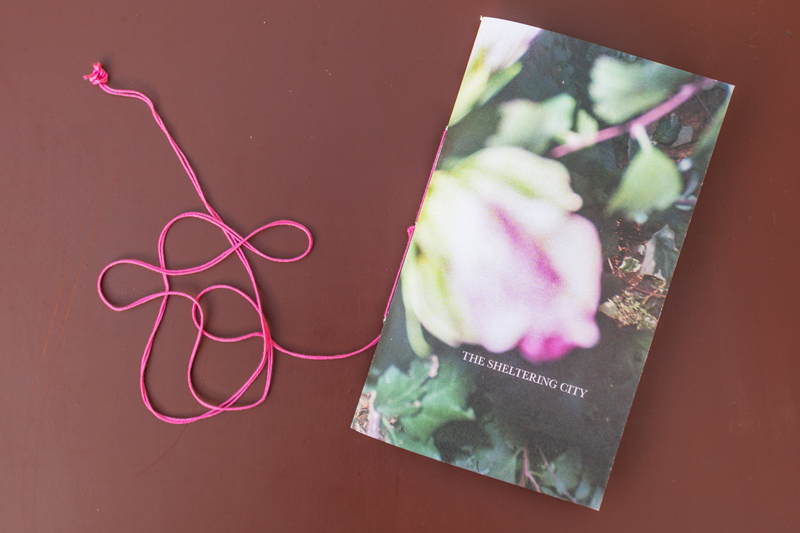

The Sheltering City – Alberta Aureli

printed in Summer 2019

Limited edition – 50 copies

44 pages – 37 photos

Softcover 13x22cm, Indigo Print on Fedrigoni Arcoprint 1 E.W. 120gr. / Fedrigoni Arcoprint 1 E.W. 250gr. ; text in Calque Satin Canson, 90gr.

Design: Alessandro Ciccarelli

price: 10€

The Sheltering City

La prima storia inizia in un bar, a Roma. Voglio partire per Tangeri e qualcuno mi dice “ah, Tangeri dei ladri” io dico no, Tangeri dei poeti. Ma non è la prima. La prima a pensarci meglio inizia sullo stretto di Gibilterra, sono a Tarifa e per arrivare in Marocco c’è solo un’ora di barca, eppure ho dimenticato il passaporto a casa. C’è un’altra storia che riguarda tutte le storie, quelle che non finiscono e passano dai libri, ai pensieri, ai fotogrammi dei film con i vampiri della notte.

A Tangeri rivedo un’amica dopo tanto, più di dieci anni, e andiamo un po’ indietro e un po’ avanti nel tempo, ci infiliamo nei vicoli stretti della Medina fino a dove riusciamo a vedere il porto e saliamo di sera sul tetto del nostro riad quando s’alza la preghiera del muezzin, “guarda, tutto è rosa e giallo”.

Burroughs e Bowles, il mito di Tangeri. Io e Chiara arriviamo con un taxi a una spiaggia famosa, ci vuole mezz’ora dal centro della città. È Ottobre, il vento è fresco e l’acqua dell’oceano è gelida, non parliamo più tra noi.

Nel libro di Bowles un uomo e una donna portano il loro amore moribondo in Marocco, definiscono la differenza tra un viaggiatore e un turista, e capiscono che l’unico modo per separarsi è morire, mentre un cielo distante continua a proteggerli. Gli amanti di Jarmusch invece non muoino mai, attraversano i secoli e la città in una paralisi senza fine.

Andavamo a Tangeri perchè lì, in un modo o nell’altro, era più facile sparire.

Il proprietario del nostro riad è un uomo elegante che da Parigi è arrivato qui negli anni settanta, dice che la cosa migliore da fare oggi è non fare niente. Noi invece camminiamo perchè abbiamo troppo poco tempo e troppa paura di sprecarlo. A cena, di sera, mischiamo ancora i racconti delle persone che conosciamo, come sono andate a finire le loro vite, almeno fino a qui.

Solo molto dopo il mio ritorno penso a come ricostruire tutto in una narrazione unica, e se è possibile che qualcosa abbia mischiato ogni parola e ogni inizio di, in una storia sola.

A chi gli chiedeva perché avesse passato gran parte della sua vita a Tangeri, Paul Bowles rispondeva: «È stato un caso». Poi aggiungeva che, rispetto ad altri posti, era «meno intaccata dagli aspetti negativi della civiltà contemporanea». E se proprio era in vena di confessioni, raccontava che lo affascinavano i musicisti jilala che cadevano in trance, e «la rete di cunicoli invisibili che la stregoneria scava intorno al sonno».

The Sheltering City

The first story begins in a bar in Rome. I want to go to Tangier’s. “Tangier’s of Thieves” someone says. I say no, a “Tangier’s of poets“. But this is not the first one. To think of it better the first story starts on the Strait of Gibraltar, I am in Tarifa planning to catch the one-hour sail to Morocco by ship, but I have forgotten my passport at home. There is another story that concerns all the stories, those that do not end and pass from books, to thoughts, to frames in a movie with the vampires of the night.

I meet a long-lost friend in Tangier’s, it has been 10 years since we were last together and we jump back and forth in time. We wander the narrow alleys of the Medina, untill where we can catch a view of the harbour below. In the evening we go on the roof of our riad when the prayer of the muezzin rises, “Look, the sky glows in all the hues of pinks and yellows”.

Burroughs and Bowles, the myth of Tangier’s. Chiara and I take a 30-minute taxi ride out from the city centre to a famous beach. It is October, the wind is freezing, the ocean cold, we do not talk to each other anymore.

In Bowles’ book a man and a woman bring their dying love to Morocco. They define the difference between a traveller and a tourist. They understand the only way to break-up is to die, while a distant sky continues to protect them. Jarmusch lovers never die, they cross the centuries and the city trapped in an endless moment.

We went to Tangier because there, in one way or another, it was easier to disappear.

The owner of our riad, an elegant man who arrived from Paris in his seventies, tells us the best thing to do is to do nothing. Instead we walk, we have too little time and do not wish to waste any. In the evening at dinner, we still mix the stories of people we know, how their lifes ended up, at least so far.

Only a long time after my return from this trip, I think about how I could reconstruct it all into a unique narrative and if it is possible something has mixed up every word, every beginning of/in a single story.

When someone asked him why he had spent most of his life in Tangier, Paul Bowles replied, “It was a coincidence.” Then he added that, compared to other places, it was “less affected by the negative aspects of contemporary civilization”. And if he was in the mood for confessions, he said that he was fascinated by the Jilala musicians who fell into a trance, and the network of invisible tunnels that witchcraft digs around the sleep.”

Alberta Aureli